CERTIFICATE IN GLOBAL HEALTH RESEARCH

Course 10: Designing Quality Health Survey Questions

The crux of research lies not only in the aim of the study, but also in the data collected. When conducting quantitative and qualitative research, the design of survey questions is instrumental in obtaining quality data. Research is a vehicle for creating knowledge. Drawing incorrect conclusions from research, particularly in health related studies, can have an impact on findings themselves, but more importantly on the implications and recommendations for improving patient care or community programs.

What makes a quality health survey? Why is it necessary?

Disseminating pertinent information regarding the burden of disease and risk factor trends is the purpose of health surveys(1). Health research over the last several decades has influenced mortality rates, communicated messages of practicing healthier lifestyles and engaging people in disease preventative activities.(2) The effect that data quality has on these aspects is contingent on many factors. Ensuring reliability, accuracy of data tools, representative samples, and the validity of participant responses, are the challenges faced by health surveys. (3)

Whether verbal or written, surveys are a method to obtain an understanding about public opinion and perceptions. In the wider realm of sociology, politics, economics, behavioural psychology and across industries, statistical research is used to uncover the underlying ‘truth’(4). As part of conducting a research study, the design of data tools is as important as selecting the right methodological approaches. Appropriate attention should be given to the proper development of the instruments used to collect data. Why? It is essential to avoid creating gaps between the theoretical postulates of research and the language used to find the facts. (5)

Developing Quality Surveys: Design Guide

It is important to select the most appropriate method for your research. “Quantitative research techniques such as surveys enable the gathering and analysis of a large number of views about certain issues. They generate numerical data about the number of people who think about a topic in a particular way. Approaches such as focus groups and interviews are examples of qualitative research. They provide an in-depth examination of views and opinions and provide stories and narratives from the people taking part”.(6)

Table 1

(Picker Institute Europe, 2009)(7)

What to do

When it comes to developing health survey questions, it is important to first determine the directionality of your intended research. Taking time to plan your survey questions can help to eliminate discrepancies in research results, as well as generate focused and specified data.(8) It is also important to incorporate validity and reliability in the questions chosen. According to Aday & Cornelius,(9) survey questions about health or topics related to health involve the following steps:

decide how to measure the concepts

relate the concepts to the survey design and objectives

match the scale for the measures chosen to the analysis plan

evaluate the reliability of the measures

evaluate the validity of the measures

choose the most appropriate method of data collection

tailor the measures to the study sample

decide how best to ask the actual questions

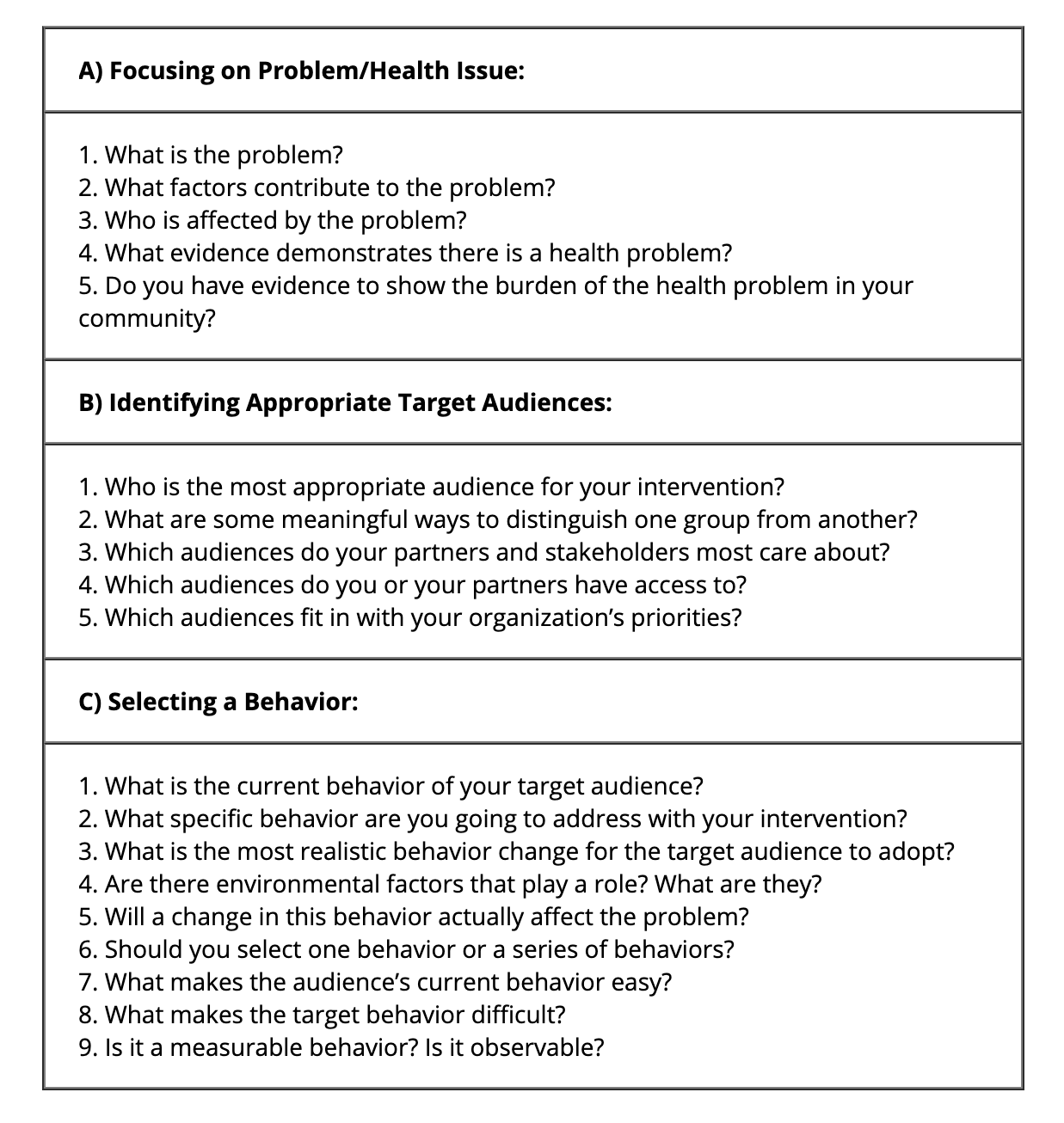

Exploring deeper into Step 8 yields three categorizes that will assist in focusing and creating precisely the right type of questions to ask – a) the problem/health issue, b) the target audience and c) the specified behaviour wanting to be captured. Table 2 illustrates a list of potential questions that can assist with the process of developing initial research objectives. (10)

Table 2: Mapping out health survey questions (adapted from CDCP 2010)(11)

Writing accurate questions is vital to collecting accurate data. Non-sampling error can occur when writing questions by inadvertently leading respondents to give a specific response.(12) Willem & Irmtraud agree that “first, it is crucial to determine what needs to be studied.”(13) Thus, it is pertinent to know the concepts behind the questions being asked. For example, consider the question“the satisfaction with the work of the present management” versus “the amount of hours people work normally”. The first question attempts to capture a feeling about the management, while the second is more factual information about work. (14)

Concept: I am (very) (dis)satisfied with the work of the present management

Question: Are you satisfied or dissatisfied with the work of the present management?

Concept: Normally I work x hours.

Question: How many hours do you work normally?

There is a smaller margin of error demonstrated with these concepts, but one can see how the way questions are asked and responses obtained are anchored by the relevancy of the concepts to which it is connected. As seen in the above example, tone can play a crucial part in how questions are not only interpreted, but answered. Again, research goals and objectives should be aligned with the methodology of the study. Additional items to keep in mind when writing survey questions are: time reference, saliency, and centrality. (15) Time reference is described as the length of memory recall time that respondents are asked in questions, ie. last week, one month, or three months ago. Saliency or centrality refers to the common occurrence where respondents do not choose extreme answers. For example, when given the options of “agree, neither agree nor disagree, and disagree,” respondents are less likely to choose the more extreme responses of “agree” and “disagree.”(16)

The Social Context

There are varieties of factors that can contribute to significant errors in research studies. To help steer away from these, it is especially important to minimize the influence of participant bias, or what is commonly referred to as self-reported measures. These include issues such as social desirability bias, self-evaluation bias and forgetfulness, all of which can affect the outcome and validity of data.

In health surveys, it can be difficult to differentiate between actual and reported behavior by patients. Caution should be used when dealing with self-reported measures since “the ability of [even] the physician to identify which persons are poorly adherent from their self-report or from other subjective clues is poor”. These biases can be minimized primarily by questionnaire and survey design that carefully considers overall questionnaire structure, the method of administration, the length of recall time used, and the type of activity being reported.(17)

What makes a good question?

The primary elements to a survey are the questions and the format used for the response. (18) Questions should not be too lengthy, and it is important for the questions to be clear. The researcher should always utilize standard language and leave out scientific jargon or words that are lengthy and make the meaning of the question unclear.(19)

Prior to many research activities, pre-testing or piloting questions in focus groups can prove to be very beneficial in creating the right questions for specific issues. By identifying factors within the responses, it will help to develop consistent data and remove redundant questions.(20) This serves as a test to ensure that the meaning of the questions are interpreted in the same way by respondents as they are by the researcher.(21) This allows for reliability testing as well as eliminating any discrepancies or potential biases that may be present before utilization in the field.

Additionally, the context effect can influence survey responses, (22) since it can impact how respondents perceive and answer the questions. (23) Questions should be asked in the order of increasing sensitivity as a way to build a level of comfort with the respondents.(24)

Types of Questions

Leading questions are problematic

A researcher can, at times, get too involved with their study and blur the lines of the procedures that must be followed. Especially when working with vulnerable populations or those with low levels of education, investigators may tend to impose their own beliefs, attitudes and perceptions on respondents, thereby creating leading questions and behavior. However, questions can be framed in a way that ensures that respondents are providing responses that reflect their personal beliefs. We will review several examples of effective and ineffective survey design from a published research study.

Original survey question: “Do you know that people are testing a vaccine against hook worm?”(25)

Concerns about this survey question: First, this type of information should be included in the informed consent that every participant will receive prior to voluntarily participating in the study. Second, including the correct response in the question leads a higher proportion of respondents to agree with it. The question does not assess whether the respondent was actually aware that researchers were testing a vaccine against hook worm.

Re-phrased survey question: “Do you know what is being tested?” If the respondent replies “yes,” the next question should ask “What is being tested?”

Original survey question: “Are the researchers doing good work in your community?”

Concerns about this survey question: This question, which is being asked by a researcher, leads to the respondent to agree that good work is being done by the researchers. Indeed, 100% of the respondents responded “yes” in response to this question in the research study.

Re-phrased survey question: “Do you believe that the researchers will have a positive or negative impact on your community?”

Original survey question: “Do you know what a vaccine does?” (26)

Concerns about this survey question: This type of question cannot be utilized to assess whether the respondent actually knows what a vaccine does. A follow-up question is necessary to assess actual knowledge.

Re-phrased survey question: “Do you know what a vaccine does?” If the respondent responds yes, then the follow-up question must be “What does a vaccine do?”

Original survey question: “Have you heard of amarelao?”(26)

Concerns about this survey question: This type of question does not assess whether the respondent has actually heard of amarelao (hookworm), and the question also does not assess the more important question of whether the respondent knows facts about hookworm.

Re-phrased survey question: “If someone has amarelao, what signs or symptoms do they usually show”? The researcher should record the response and determine if the response is accurate. This enables the researcher to determine if the respondent has heard of amarelao, and if the respondent is familiar with facts about amarelao.

Indirect Questions

Indirect questions have been shown to reduce social desirability bias on variables that have a tendency to be socially influenced. (27) The underlying notion is that respondents will depict behavior of other individuals in the particular scenario, but are actually projecting their own unconscious biases of behavior to the same situation. (28) Therefore, they are ultimately describing their own impression, opinion or feeling, using the façade or perspective of ‘another person’.

Example: Will your family respond favorably or unfavorably if you receive medical treatment?

Two-Part Questions

The respondent may answer yes to the first part and no to the second, or vice versa. “Would you like to receive surgery, and would your family like you to receive surgery?” Separate this type of question into two items.

Important Considerations

Personalization may improve response rates to surveys, but may also result in a higher degree of socially desirable responses.(29)

An option for precluding bias questions may result in questions that provide the option of “no opinion”. However, beware that this too can have a profound effect on data quality. Including this type of answer choice doesn’t increase the data quality and can often eliminate the opportunity to capture significant information or opinions.(30) Sources of potential bias in non-response questions mainly occur when asking about health behaviors (ie. physical activity, smoking, drug and alcohol use, wearing condoms, wearing helmets or seatbelts, use of insecticide treated bed nets, etc.), social status (primarily income), witnessing violent acts, and gender or age differences (male versus female responders).(31)

Do not feel that large budgets and more funding create a better quality survey. Good survey design requires and utilizes the same fundamental principles regardless of the size of the survey. (32)

It should be noted that cultural values provide important insights, and these nuances are also important to research results. Therefore, reducing or controlling for social desirable biases may be inappropriate in some instances.(33)

Refer to similar studies for conceptual frameworks to help guide the development and selection of survey material(34). By reviewing similar articles and questionnaires, a relevant summary of research methods and results can be provided. (35) Keep in mind, however, that published research studies in peer-reviewed journals do not necessarily utilize quality survey design, and it is therefore important to carefully consider the validity of each question in a research study. For example, a model predicts that 80% of non-randomized studies “turn out to be wrong, as do 25 % of supposedly gold-standard randomized trials, and as much as 10 % of the platinum-standard large randomized trials.”(36)

Appropriate interview techniques have an impact on the quality of results, especially when working cross-culturally and in different languages. Overall, valid data can inform the development of policy and provide the opportunity for culturally appropriate interventions to be designed and implemented. (37)

Practical Surveys: Research in Action

In a study illustrating socially desirable answers to drug use, researchers verified the self-reported behavior against validation of the Crowne–Marlowe scale.(38) The conclusions of the study could not be definitive due to the distortion of answers. This kind of information bias is also prevalent in studies focusing on sexual health behaviours, mostly involving contraceptive use or family planning methods. The efficacy of such research relies on self-reported data that is not credible and therefore attempts to utilize a more objective approach in order to obtain accurate measurements.(39) Strategies to reduce study bias include comparing subjective and objective data and highlighting deficiencies in the collected subjective data; administering anonymous self-administered questionnaires; and providing participants with methods that ensure privacy and confidentiality.(40)

The Future of Health Surveys

There is no doubt that “health surveys have been and will continue to be important sources of information for health care policymakers, public health professionals, private providers, insurers, and health care consumers concerned with the planning, implementation, and evaluation of health-related programs and policies. The design and conduct of health surveys in the future will be shaped by changes in the diversity, complexity, and sensitivity of the topics addressed in these studies; the innovative techniques and technologies that are being developed for carrying them out; and the new or intensified ethical dilemmas that are a result of these changes.” (41) By creating and conducting health surveys that are firmly based on quality techniques, researchers today can help form the outcomes of tomorrow.

Footnotes

(1) Wilks R., Younger N., Mullings J., et al. (2007) Factors affecting study efficiency and item non-response in health surveys in developing countries: the Jamaica national healthy lifestyle survey. BioMed Central Medical Research Methodology 7 (13).

(2) Nelson D.E., Kreps G.L., Hesse B.W., et al. (2004) The health information national trends survey (HINTS): development, design, and dissemination. Journal of Health Communication 9, 443-460.

(3) Wilks R., Younger N., Mullings J., et al. (2007) Factors affecting study efficiency and item non-response in health surveys in developing countries: the Jamaica national healthy lifestyle survey. BioMed Central Medical Research Methodology 7 (13).

(4) Willem E.S. & Irmtraud N.G. (2007) Design, evaluation, and analysis of questionnaires for survey research. John Wiley & Sons Inc, New Jersey.

(5) Ibid.

(6) Picker Institute Europe (2009) Using patient feedback. Picker Institute Europe, Oxford.

(7) Ibid.

(8) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2010) Social Marketing for Nutrition and Physical Activity. http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpa/socialmarketing/training/basics/planning_questions.htm.

(9) Aday L.A. & Cornelius L.J. (2006) Designing and conducting health surveys: a comprehensive guide, 3rd ed. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco.

(10) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2010) Social Marketing for Nutrition and Physical Activity. http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpa/socialmarketing/training/basics/planning_questions.htm.

(11) Ibid.

(12) Brace I. (2008) Questionnaire design: how to plan, structure and write survey material for effective market research, 2nd ed. Kogan Page Limited, London.

(13) Willem E.S. & Irmtraud N.G. (2007) Design, evaluation, and analysis of questionnaires for survey research. John Wiley & Sons Inc, New Jersey, 83.

(14) Ibid.

(15) Ibid., 84.

(16) Brace I. (2008) Questionnaire design: how to plan, structure and write survey material for effective market research, 2nd ed. Kogan Page Limited, London.

(17) Adams S.A., Matthews C.E., Ebbeling C.B., et al. (2005) The effect of social desirability and social approval on self-reports of physical activity. American Journal of Epidemiology 161 (4), 389-398.

(18) Aday L.A. & Cornelius L.J. (2006) Designing and conducting health surveys: a comprehensive guide, 3rd ed. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco.

(19) Ibid.

(20) Buckingham M. & Coffman C. (1999) First, break all the rules: what the world’s greatest managers do differently. Simon & Schuster, New York.

(21) Aday L.A. & Cornelius L.J. (2006) Designing and conducting health surveys: a comprehensive guide, 3rd ed. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco.

(22) Ibid.

(23) Ibid.

(24) Gregson S., Zhuwau T., Ndlovu J. & Nyamukapa C.A. (2002) Methods to reduce social desirability bias in sex surveys in low-development settings: experience in Zimbabwe. Sexually Transmitted Diseases 29 (10), 568-575.

(25) Gazzinelli M.F., Lobato L., Matoso L., et al. (2010) Health education through analogies: preparation of a community for clinical trials of a vaccine against Hookworm in an endemic area of Brazil. Public Library of Science Neglected Tropical Diseases 4 (7), e749.

(26) Ibid.

(27) Fisher R.J. (1993) Social desirability bias and the validity of indirect questioning. The Journal of Consumer Research 20 (2), 303-315.

(28) Ibid.

(29) Heerwegh D. & Loosveldt G. (2007) Personalizing e-mail contacts: its influence on web survey response rate and social desirability response bias. International Journal of Public Opinion Research 19 (2), 258-268.

(30) Krosnick J.A., Holbrook A.L., Berent M.K., et al. (2002) The impact of “no opinion” response options on data quality: non-attitude reduction or an invitation to satisfice? Public Opinion Quarterly 66, 371-403.

(31) Wilks R., Younger N., Mullings J., et al. (2007) Factors affecting study efficiency and item non-response in health surveys in developing countries: the Jamaica national healthy lifestyle survey. BioMed Central Medical Research Methodology 7 (13).

(32) Aday L.A. & Cornelius L.J. (2006) Designing and conducting health surveys: a comprehensive guide, 3rd ed. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco.

(33) Fisher R.J. & Katz J.E. (2000) Social-desirability bias and the validity of self-reported values. Psychology & Marketing 17 (2), 105-120.

(34) Nelson D.E., Kreps G.L., Hesse B.W., et al. (2004) The health information national trends survey (HINTS): development, design, and dissemination. Journal of Health Communication 9, 443-460.

(35) Aday L.A. & Cornelius L.J. (2006) Designing and conducting health surveys: a comprehensive guide, 3rd ed. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco.

(36) Freedman D.H. (Nov. 2010) Lies, Damned Lies, and Medical Science. The Atlantic Magazine. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2010/11/lies-damned-lies-and-medical-science/308269/.

(37) Wilks R., Younger N., Mullings J., et al. (2007) Factors affecting study efficiency and item non-response in health surveys in developing countries: the Jamaica national healthy lifestyle survey. BioMed Central Medical Research Methodology 7 (13).

(38) Johnson T.P. & Fendrich M. (2002) A validation of the Crowne-Marlowe social desirability scale. University of Illimois, Survey Research Laboratory, Chicago.

(39) Stuart G.S. & Grimes D.A. (2009) Social desirability bias in family planning studies: a neglected problem. Contraception 80, 108-112.

(40) Ibid.

(41) Aday L.A. & Cornelius L.J. (2006) Designing and conducting health surveys: a comprehensive guide, 3rd ed. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, 2.